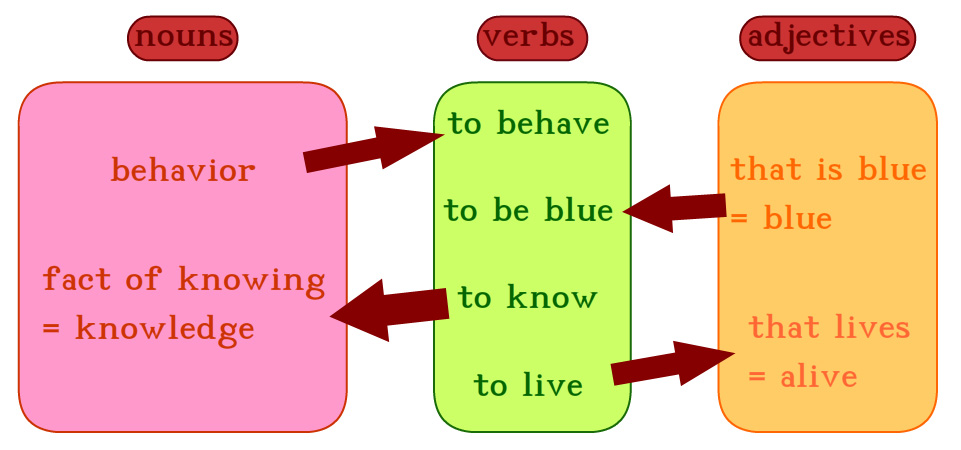

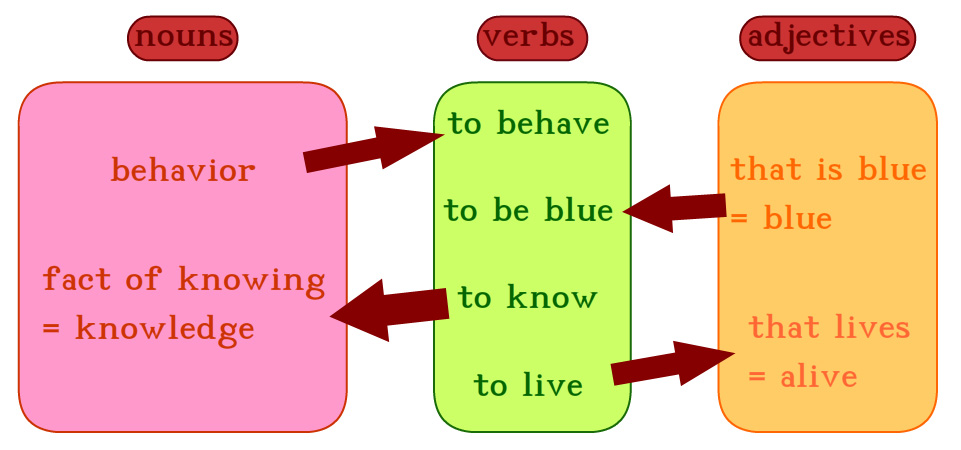

^ relation words transfer system between categories

Poplengwo version 3

This article deals with the 3rd version of Poplengwo. The next paragraphs of introduction will be recounting the history of the creation of this new version (isolating language), built from the previous version: Poplengwo version 2 (agglutinative language). If you want to check out the grammar of this new version, I advice you to directly read the part about grammar. It is easier to understand and will avoid you to get comfused with grammatical classes.

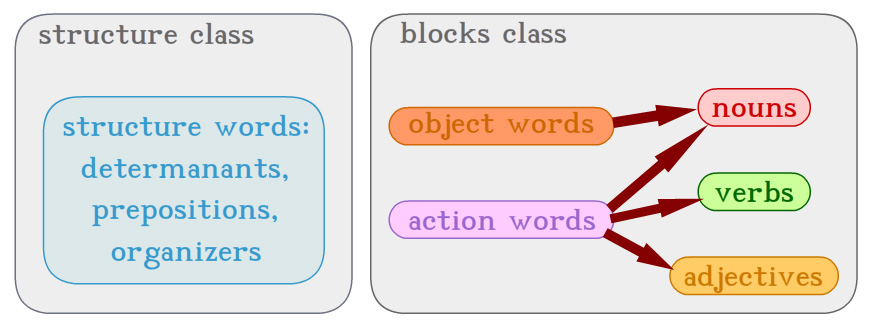

The problem in version 2 was the difficulty to design new words from natural languages with a certain vowel at the end. (<o> for nouns, <i> for verbs...) It was especially hard with original chinese words that often already ended with a vowel, even sometimes a diphtong. The words obtained then were either quite unelegant to pronounce, or, when modified to be easier to pronounce, they often didn't look like the original word enough to be regognized by a chinese speaker. The main change here in version 3 is therefore to abandon version 2's word ending rules, and find another way to easily determine the category of words. This is a quite huge work at the begining, as we have to rebuild the whole structure of the language, but it will allow more freedom in designing new words. So one solution would be to determine the category of words according to their number of syllables or their number of letters, prepositions and organizers having few syllables or few letters, and other words having more, but this solution would be less efficient than the older one. You cannot allocate one category of word to one word length, though: it imposes too much constraint to the design of words and it is even not easy to determine the words lengths with just a glance. Imagine: you would have to count every syllable or letter of every words to determine their categories and then understand the whole sentence! Let's just use an intermediate way: accordingly you can hardly differenciate words with 1, 2, 3 syllables or letters, yet you can easily tell apart monosyllabic and multisyllabic words, as you hear them, or one letter words and many letters words, as you read them. So we will first have to make the choice between those two solutions. I think it is more appropriate to allocate short word lengths to prepositions and organizers (formerly <u> and consonnant ending words), and long word lengths to verbs, nouns, adjectives and preverbs (formerly vowel ending words except <u>). This coarse classification between only two groups compels to find new tricks to differenciate word categories within both groups. By the way, this classification, originally determined intuitively by the number of words of same category (there are much fewer prepositions and organizers than there are other kinds of words), is moreover accurate for another reason. Indeed, in the "small words" group, prepositions are in a way kinds of organizers, so the formers and the latters get together well. Prepositions are just there to announce an argument. They play a role in the structure of the sentence, as do organizers. I shall call this group the structure class. Words from this class correspond to Lojban's cmavo. As well, in the "big words" group, words all have the charactristics to derivate from one another across the categories, and they have meanings related with reality. As they are the "building blocks" which make up the sentence and are linked with structure words, I shall call this group the blocks class. Words from this class correspond to Lojban's brivla. Now, there will remain to find a way to differenciate prepositions from organizers, and eventually to deal with differenciating categories of words from the blocks class.

First, should we detremine words lengths according to syllables or to letters. To my mind, the syllables method would be better, as syllables are easy to identify when the sentence is heard, as well as they are quite easy to count when reading: you just need to count the vowels. It is also demonstrated in this article that a word must always have at least one syllable, ie one vowel. So here is the first great rule for version 3: Monosyllabic words belong to the structure class and multisyllabic words to the blocks class. However, you will see it is not this simple.

Second, how to distinguish prepositions from organizers? As there are only two groups to separate, we could simply say: preposition end with a consonnant and organizers end with a vowel, but another rule, coming later, prevents it and you will see that every structure words must end with a consonnant. And, when you think about it, as long as you know the words you hear or read, and you are used to them, you do not need to notice: "This one is a preposition." or "That one is an organizer."

Third, the hardest part, how to distinguish categories within the blocks class? Remember that we do not want to impose a certain letter at the end of the words. This rule was precisely the starting point of this version 3. After having thought of it for a while, the only passable trick I found is inserting new "prepositions" or "determiners" before the word to indicate its category. I shall call them determiners because they determine the category of the following word. The difference between prepositions and determiners is that prepositions apply to a whole argument in the sentence and determines its function, whereas determiners only apply to an adjective or a noun complement inside an argument. Now, you can already see how we are going to recede back to an isolating language. Don't worry, it will not be any longer to write or to pronounce than in version 2. So the third great rule of version 3 reads as follows: an adjective shall be preceded by the adjective determiner. So simple rule! And you will see it is enough for I planned the rest. I would gladly have used "a" for this adjective determiner, because you find again the <a> of the end of adjectives in previous versions, and also, "a" like "adjective", but later modifications, resulting in new rules, prevented me from doing this. Bad consequence to this trick of prepositions: every single argument has to be preceded by a preposition, so that you do not mix it up with the verb. Even the subject has to carry its own preposition. Hence this new-born word in version 3: "el". Good consequence: no need to invent different words for verbs, nouns and adjectives. A same word can be used with different categories. It only has to be at least two syllables long.

After having tried to imagine sentences with those new rules, you can quickly notice that it is quite inconvenient to use pronouns with at least two syllables. We are then forced to infringe the rule (that was too good to be true) "short words = structure words, long words = block words". But now we really have to make a difference between pronouns and structure words. I will then restrict the structure class to monosyllabic words ending with a consonnant, that is why I cannot use "a" for the adjective determiner. This way, we are able to create monosyllabic pronouns, as long as they end with a vowel. I have now to change all the organizers and determiners, to make them end with a consonnant. Just check out the rest of the article to see what more I modified from the previous version and how.

Notes: The choice to make block words end with any kind of letter made it impossible to add suffixes. That is the real reason why version 3 had to become an isolating language again, although it came from version 2 which was an agglutinative language. Thus, you may find in this version some ideas taken from version 1.

Orthography

Poplengwo is a written and spoken language, as every official human language is spoken and mainly written. To maximize the simplicity, the speaking and writing systems must correpond perfectly: Each sound is allocated to one symbol, and vice versa. And, since the latin alphabet is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world, it is accurate for a good international language. Here is Poplengwo's alphabet and the pronounciation of each of the 25 letters:

a [a]/[ɑ], b [b], c [ʃ]/[ʂ], d [d], e [e]/[ɛ], f [f]/[ɸ], g [g], h [h], i [i], j [ʒ]/[ʐ], k [k], l [l]/[ɭ], m [m]/[ɱ], n [n]/[ɳ]/[ŋ], o [o]/[ɔ], p [p], r [r]/[ɾ]/[ɹ]/[ʀ], s [s], t [t], u [u], v [v]/[β], w [w], x [x], y [j], z [z].

Note: Only the five red letters are considered as vowels in Poplengwo. The rest are consonnants.

As graphemes and phonemes must be perfectly equivalent, there is no need for capital letters to appear in the words of our international language. Therefore, every word will be lower-case. However, any kinds of other symbols may be used for abbreviated writing.

When you hear a sentence in this language, the spaces between words are not pronounced: they don't stand for a pause like a comma or a point do. So, in order to distinguish words from one another, the trick is to add stresses on them. We put the stress on the whole word except on its last syllable. e.g. "foni" ['foni], "ameriko" ['a'me'riko] Consequently, the monosyllabic words are not stressed. This method makes it possible to distinguish words from one another in a sentence. e.g. [moan'a'ploso'hawi] -> "mo an aploso hawi". For this method to work infallibly, words with no vowels (like in Russian) must not exist, for you wouldn't be able to tell that it is a full-fledged word. e.g. "l wo" and "lwo" would be pronounced exactly the same. What's more it would often be pretty hard to pronounce when the previous word ends with a consonnant and the next one begins with a consonnant too. In short, all words must have at least one syllable.

To separate sentences from one another, we use a point that means that we must pause for a short while before saying the next sentence. The point is surrounded by two spaces. (A text will look like this: "sentence1 . sentence2") If a sentence is the last one of a text, it doesn't need a point at its end because there is no other sentence after it, that's why a text will normally finish (and begin as well) with no punctuation sign. There also exists an excamation mark. It is useful to emphasize a sentence and it will be pronounced louder or more high-pitched than a normal sentence, but even if the whole sentence is more high-pitched, the relative stresses in the words must remain. For readers to know how they have to pronounce a sentence before reading it, the possible exclamation mark will be written just before it. It replaces the point that would be there by default and takes exactly the same place. Yet, in opposition to the point, the exclamation mark can be present at the very beginning of a text, not only between two sentences. Commas can be introduced into a sentence to symbolize a pause (that must be shorter than the pause of a point). They take the same place as a point between two words, that is, there are spaces before and after it. (This is to standardize the punctuation typography.) The interrogation mark doesn't exist. Questions will be expressed with particular words.

Grammar

Introduction

Basically, what is language for? One would extempore answer it is used for communicating. So what is communication for? Actually, every time you say or write something, the purpose of this is to act on the world. For example when you say "Give me a coffee please.", you make someone do somethink for you. It may seem that you only act on the world when you give an order or make a request, but in fact, you also act on it when uttering a simple affirmation. Indeed, an affirmation is nothing else than a request for someone to know something, and you can translate any affirmation into a request, e.g. "I am happy." translates to "Know that I am happy." Also, a question is just a request for someone to answer it, e.g. "What are you doing?" translates to "Tell me what you are doing." So, if we wanted to create a perfectly logical language, we should always use this pattern for every sentence, that is to say make a request with an explicit verb like in the previous sentences: "give", "know", "tell" or whatever you like. (I think that Lojban is not even logical enough to use such sentence patterns...) You will agree that this kind of structure would be pretty tedious to use, and in every natural language, we favour a more implicit yet simpler structure which is not less comprehensible. That is why we are going to do the same in Poplengwo. There is another point about the logical structure of a sentence that should not be forgotten. When you make that request in a sentence, there should be a precision about who is requested to do something, otherwise the request would be ambiguous if there are more than one person in the surrounding area. Still, as before, precising the destination of the message every time you talk would be quite annoying, so we will also often leave this out, in case the destination is obvious. Should the opposite occur, Poplengwo allows you to precise the destination thanks to a preposition: "hey".

The sentence

Fundamentally, a sentence is the expression of a relation between a certain number of arguments. It has to express the required arguments and, above all, the name of this relation. Let's call this type of word a verb. This is actually the very core of the sentence. In order to understand my explainations well, you will have to forget the meaning of grammatical words you knew, because I will use them with a different meaning, though I will define what I am talking about everytime I use a new word. For example, here, what I call a verb is not a category of word, but the role that a word plays in the sentence. So a sentence is composed of a verb, corresponding to Lojban's selbri, and some arguments, corresponding to Lojban's sumti, that link to the verb. In order to make the difference between the verb and its arguments, every argument is preceded by a preposition that determines its function in relation with the verb. The most basical way to form an argument is to put a preposition and then put what I will call a noun. A noun is an elementary entity that can act as a n argument. There are three categories of words. Some words can be used as a verb, I will call them relation words. They correspond to Lojban's brivla. Others are bound to play the role of nouns, I will call them object words. They correspond to Lojban's cmene. As both relation and object words have the characteristics to have a meaning in reality, and to play the role of the "building blocks" of the sentence, I will classify them in a set called blocks class. There is eventually a third category of words: the structure words, corresponding to Lojban's cmavo, like for example prepositions. I will classify these in a set called structure class. Although object words are bound to be used as nouns, action words can be used either as verbs, or as nouns, or even as adjectives. Every monosyllabic word ending with a consonnant belongs to the structure class. Any other word belongs to the blocks class. Monosyllabic words ending with a vowel are neither relation words, nor object words. They are pronouns and they will be explained in the section about pronouns. Therefore, every relation words and object words are multisyllabic.

Relation words

They have at least two syllables, ie they contain at least two vowels. A relation word designates a relation. It is initially designed to play the role of a verb, but can also play several roles in the sentence. You can use it as a noun. In that case, the noun means "the action to do what the word meant as a verb". e.g. "tcangi" used as a verb means "sing(s)" or "am/is/are singing", and used as a noun means "to sing" or "singing". You can also use it as an adjective. The adjective obtained this way qualifies something that makes the action described by the word, or that presents the state described by the word. e.g. "viti" used as a verb means "live(s)" or "am/is/are living", and used as an adjective means "alive". "blui" used as a verb means "am/is/are blue" and used as an adjective means "blue". Now, why have I chosen the meaning of the verb to define the meaning of nouns and adjectives, and not the opposite? First, because verbs are the only essential words of a sentence, so they need to be the first created. And they are moreover the only words from which you can define nouns and adjectives, like I did, which you cannot do in the other way. We can justify this rule with the example of "live". Indeed, we can define "life" as the action of "living" but it is unpossible to define "to live" from "life".

^ relation words transfer system between categories

Here is a list of some relation words I will be using in examples:

ai = to love [someone]

ara = two

hixwan = to like

dongi = to know [something]

drinki = to drink

esi = to be [identity]

esti = to be [place]

eti = to eat

foni = to phone

goi = to go

lua = green

redi = red

renji = to know [someone]

severa = several

sie = to die

sliip = to sleep

strangi = strange

studi = to learn / to study

tcangi = to sing

Object words

They have at least two syllables, ie they contain at least two vowels. An object word is bounded to be used as a noun only. Therefore, every word you will use as a noun and that does not designate an action, is an object word.

When speaking, you may frequently wish to use some proper names. To use a proper name, you have to transcribe it into Poplengwo's orthography, making so that the pronounciation is the nearest possible to the original one, and it has to be preceded by the determiner "il" to precise that this noun is a proper name. Proper names can sometimes have only one syllable, which provides exceptions to the rule "Object words are monosyllabic".

Here is a list of some object words I will be using in examples:

apel = apple

banan = banana

cui = water

dia = day

nano = man / male

skulo = school

tyano = sky

zio = child

Structure words

They are monosyllabic, ie they contain only one vowel, and they end with a consonnant. There are three kinds of structure words. determiners are used to determine the category of the following word or group of words. Prepositions are used to determine the function of an argument. And finally, sentence organizers or simply organizers are used to organize the sentence. To be able to talk about all this, I first need to precisely explain the structure of a sentence.

Poplengwo is made up to allow words to appear in any order you want, so that you can emphasize one, putting it at the begining or at the end for example, although there is maybe one order that is the most logical. So if such moves are allowed, the words must be marked with some other word, so that we know whether it is the subject, an object complement, a place complement, etc. All the arguments are marked with a different preposition, depending on their function. You recognize a part of the sentence as an argument because it has a preposition before it, and you recognize a verb because it has no preposition before it. The prepositions are always placed before the nominal group. For example, the preposition "an" is used to introduce an object complement. e.g. "el mi an apel hixwan" or "el mi hixwan an apel" or "an apel el mi hixwan" or "an apel hixwan el mi" or "hixwan el mi an apel" or "hixwan an apel el mi" = "I like apples." After the preposition, we can have at most one noun and any number of adjectives and noun complements. As well, you recognize a group of words as being an adjective or a noun complement because it is preceded by a determiner, and you recognize a noun because it has no determiner before it. In this way, we obtain a nominal group that would look like this ("0+" means "zero or more"):

[0+ [determiner [adjective or noun complement]]] [1 noun] [0+ [determiner [adjective or noun complement]]]

Note: The determiner will determine whether what follows is an adjective or a noun complement.

An argument (corresponding to Lojban's sumti) is composed as follows:

[preposition [nominal group or subordinate proposition]]

Note: The preposition will determine whether what follows is a nominal group or a subordinate proposition.

Now, a proposition or predicate (corresponding to Lojban's bridi) would look like this:

[0+ arguments] [1 verb] [0+ arguments]

An entire sentence is composed of (a point or an exclamation mark and) one or several propositions linked together with conjunctions.

^ word classes, categories and their possible use

determiners

The determiant "al" indicates that the following word is an adjective. Note: Adjectives can be used to translate an -ing form, like in the example: "el zio al tcangi goi ad skulo" = "The singing child is going to school." = "The child is going to school singing."

The determiner "of" is used to introduce a noun complement. It is generally translated "of" or "'s". If that noun complement does not end the nominal group, you have to close it with "uf" which is considered as an organizer.

The determiner "il" indicates that the following word is a proper name.

Prepositions

Here are prepositions introducing a nominal group:

ab = from [geographically]

ad = to / towards [geographically]

ag = ago

an = [object marker] / by [in a passive sentence]

ant = before

at = in / on / at [time]

az = as / like

bawt = about [theme/subject]

cirk = around

dan = than / as / in relation to

dank = thanks to

den = in ...'s time

dur = for / during

eks = out of / outside

el = [subject]

far = far from

front = in front of

gens = against [physically]

hey = [destination, vocative case]

hind = behind

in = in / inside

intr = between

kon = with

kontr = against [opposition] / versus

koz = because of

mong = among

nir = near / close to

por = for / pro

post = after

sid = beside / next to

sin = without

sins = since / from

sub = under

sup = over

sur = on

til = until

trans = through

tun = (in order) to / for

yond = beyond

Here are prepositions introducing a subordinate proposition.

There are subordination conjuctions. "if" = "if" (condition, not "whether") "dat" is used to introduce any kind of completive proposition. It is generally translated "that". e.g. "el mi dongi dat el ti an mi ai" = "I know (that) you love me." Yet it can be translated in another way. When "dat" is accompanied by "ke", it is translated "if"/"whether". e.g. "el mi dongi ne dat el ti an mi ai ke" = "I don't know whether you love me." When it is accompanied with a "wh pronoun" such as "who"/"what" = "ki", "how" = "kye"..., it is not translated. e.g. "el mi dongi dat el ki an apel eti" = "I know who ate the apple." "dat" can also be translated "the fact that" in sentenced like "The fact that the sky is red, is strange." = "strangi el dat el tyano redi". The word "dat" is then useful to introduce a proposition in the place where a nominal group would normally be placed. If the proposition "dat" is not at the end of the sentence, you have to consider putting a "ik/ok" couple around the proposition (see below).

There are also relative pronouns. Those ones are composed by the basical word "hum" and possibly by a preposition just before it. e.g. "el mi renji an nano hum an apel eti" = "I know the man who is eating an apple." "el mi eti an apel an hum el mi hixwan" = "I'm eating the apple (that) I like." Note that the antecedent has to be placed right before the relative proposition.

Organizers

The sentence organizers (or simply organizers) are abstract words that are there only to link words or statements with one another, or to isolate a part of a sentence, so that its meaning is changed. First, let's see those which are used to coordinate two statements together. Here they are: "et" is the word to express the intersection of two statements, or in plain words, to say "and". It is placed between the two statements. e.g. "el mi an apel eti et el mi an cui drinki" = "I'm eating an apple and I'm drinking water." "or" is used to express the union of two statements, that is, to say "or". It is also placed between the two statements. "awt" expresses the symmetric difference of two statements, that is, one of the two statements is true, but not both. e.g "! he studi awt he sii" = "Learn or die!" We also have rhetorical operators, such as "du" = "so"/"therefore", "for" = "for"/"because", "mas" = "but", "yet" = "yet". Those organizers are placed between the two statements they coordinate. They correspond to English coordination conjunctions.

Now let's see other kinds of organizers that can act on the inner part of a statement, actually on any group of words. The organizers in question are the couple "ik" and "ok". They are useful to isolate a part of a sentence, in order to shorten it, to take off its ambiguity, or even to change its meaning. e.g. "el mi an ik apel eti ok ik cui drinki ok" = "I'm eating an apple and drinking water." "el ik nano hum an apel eti ok an mi renji" = "The man who is eating an apple knows me." If one wrote "el nano hum an apel eti an mi renji" instead, it could also be translated "The man who knows me is eating an apple." or even "The man who knows an apple is eating me.", etc. In order to quote something, you need to start your quotation with "ip" and to end it with "op". If you were mistaken with a word you said, you can get it removed thanks to the word "nop". e.g. "el mi dur dia al ara eti nop sliip" = "I ate, no, I mean I slept for two days."

At last, there is also a type of organizer that only links two words together. They are "tet" = "and", "tor" = "or" and "tawt" = "or but not and". However these organizers can link more than two words together if one of the parts next to the organizer is a "ik/ok" group. e.g. "el mi an apel tet banan eti" = "I am eating an apple and a banana." (We could also have said "el mi an apel an banan eti" here.) "el mi an apel al redi tet lua eti" = "I am eating a red and green apple." (We could also have said "al redi al lua", though.) "na esti el apel al 2 tawt 3" = "There are 2 or 3 apples."

Pronouns

They are monosyllabic, ie they contain only one vowel, and this vowel is the last letter of the word. What I call pronouns are small words that replace other words, and are very useful. Some of them take the place of a block word because it is too long, and others replace a group of words, when it would be too tedious to repeat it everytime.

Block pronouns

Here are some of them:

mi = [emisor(s)]

ti = [destination(s)]

hi = [masculine third person / people]

ci = [feminine third person / people]

li = [neuter or mixed or unknown gender third person / people]

ni = [emisor(s) + third person / people]

vi = [destination(s) + third person / people]

wi = [emisor(s) + destination(s)]

ki = who? / what?

zo = [latest referred noun (Consequently, it is often used as a reflective pronoun.)]

ho = [penultimate referred noun]

do = [antepenultimate referred noun]

fo = [referring to the latest noun marked with the adjective "fa" (see below)]

o = [artifical noun]

What is up with that last "artificial noun"? To express a relative proposition without determining a precise antecedent, we use the pronoun "o" as an antecedent. Here are a few examples:

"I know the one who is eating an apple." = "el mi renji an o hum an apel eti"

"I am the one who is eating an apple." = "el mi esi el o hum an apel eti"

"The one who is eating an apple is me." = "el o ik an apel eti ok el mi esi"

You can see in the list above that you can use the pronouns "zo", "ho" and "do" to refer to a recently used noun. Unfortunately, in most of oral or written speeches, so many nouns are used that those pronouns are sometimes not enough to refer to an oldly used word, even if this noun designates a fundamental subject of the speech. That is why another pronoun exists to refer to a frequently used noun: "fo". But in order to be able to use it, we first have to define what this noun is. This is precisely the role of the pronoun "fa": insert it inside the argument where is the noun in question when it is first mentoned, and then you can use the pronoun "fo" to refer to this noun as many times as needed. Also, we can always re-define the noun associated with "fo" by using "fa" again.

Group pronouns

"se" is used to form the plural of a noun, and replaces the phrase "al severa" meaning "several". However, there is no obligation to use it, even if there are several individuals/things. In some cases it is obvious that you are talking about something in the plural. Not using "se" does not mean that what you are talking about is singular. Besides, there exists a pronoun "yi" meaning "one" to precise the singular. "yi" replaces "al una".

When you use a verb, by default, you do not bring any precision to it, as long as there is no ambiguity, yet you can precise the tense of the action, when needed, adding the pronoun "be" for the past, "nte" for the present or "re" for the future. e.g. "foni be", "foni nte", "foni re". As well, we can construct the conditionnal form with "we" and the imperative form with "he". To express the passive form of a verb, we add the pronoun "te". When doing this, we exchange the grammatical place of the subject and the object complement. Here is a list of common group pronouns:

be [used to specify a past action]

de [designates a repeated or continual action]

dje [transition] (e.g. "renji dje" = "to get to know" = "to meet")

ge [impressive action] (e.g. "djani ge" = "to make see" = "to show")

he [used to give an order]

ka [capacity] (e.g. "el mi an ti weni ka" = "I can hear you.")

ke [adverb used like an interrogation mark, but only in closed (yes/no) questions.]

kye = how

le = less

mo = more

na = there

ne = not [used to turn a sentence into negative.]

nte [used to specify a present action]

nye = nearly / almost

re [used to specify a future action]

te [used to reverse the subject and the object complement of a verb]

wa [will] (e.g. "djani wa" = "want to see.")

we [used to specify a conditonal action]

xwa [liking] (e.g "sliip xwa" = "to like to sleep.")

To ask a question, we either add the pronoun "ke" to the proposition if it is a closed (yes/no) question, or, if it is an open question, we replace the unknown part with an accurate interrogation word. If we ask about an argument, we will use the pronoun "ki" and possibly add a preposition before it. If we ask about a description of an argument, we will use the phrase "al ki" = "which one". To ask about a relation between arguments, we will use "ki" as the verb of our question. Eventually, to ask about the way in which an action is done, we'll use "kye" = "how".

Vocabulary

In order to be easy to learn by most people worldwide, this language must take its vocabulary from word roots of the most used words in the word. Let's take a look at what natural languages we should refer to. According to Wikipedia, the list of languages by total number of speakers varies depending on whether we consider the highest estimation or the mode average estimation. In order to get the same languages in both lists, we can either reduce it to three or to ten languages. To get most precision and to keep a maximum of languages example, we will choose the lists of ten languages. These are the two lists we obtain this way:

|

Highest Estimation: |

|

|

Language |

Total number of speakers (million) |

|

English |

1800 |

|

Chinese |

1300 |

|

Hindustani |

905 |

|

Arabic |

873 |

|

French |

600 |

|

Spanish |

500 |

|

Russian |

285 |

|

Portuguese |

230 |

|

Bengali |

230 |

|

Indonesian |

200 |

|

Mode Average Estimation: |

|

|

Language |

Total number of speakers (million) |

|

Chinese |

1036 |

|

English |

618 |

|

Hindustani |

487 |

|

Spanish |

376 |

|

Arabic |

285 |

|

Russian |

278 |

|

Indonesian |

234 |

|

French |

213 |

|

Bengali |

207 |

|

Portuguese |

203 |

For every word of our international language, we will match its translation in all ten languages, and choose the one that can be understood by the majority of people. For example, if a word is simarly used by 1 billion A-speakers and by 1 billion B-speakers, and another word is used by 1.5 billion C-speakers, the A and B word root will be chosen. In most cases, if the English word has a different root than the words of the roman languages, then the Chinese word has to be chosen.